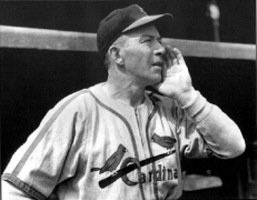

#30 Billy Southworth, Manager

By Mort Bloomberg

Clint Conatser and Tommie Ferguson were unknowingly the chief catalysts for this article because both brought up Southworth’s name repeatedly as we spoke about their years with the Braves during the late 40s and early 50s.

Said Tommie, "I loved Billy Southworth. He was great to us kids. Each season the batboys would go on a road trip of

their choice and for each city at which the team stopped, Billy gave me 50 cents for a milk shake. That was in addition to the meal money Duffy Lewis [road secretary] would furnish -- $6 per diem."

Said Clint, "I thought a lot of him and found him very personable. Spahn and a few other guys on the team said that Billy had

confided that I reminded him of his late son. But I wasn’t privy to that. All I know is that he was good to me. Thanks to him I had a chance to play in the major leagues plus reach the World Series, as a rookie no less. So I am grateful to him."

It was his sense of fairness and honesty that had the biggest impact on Roy Hartsfield, when I asked him at the 2007 BBHA

dinner/reunion about Southworth. "He made it as easy for me as he possibly could. At my first spring training with the Braves in 1950 down in Bradenton were four second basemen: Connie Ryan, Sibby Sisti, Gene Mauch, and I was #4. When we started playing exhibition games he gave each of us a shot at the position. Ryan was the #1 choice so he would get the first game and then down the line to me and we would rotate each game until we broke camp in late March. He couldn’t be any fairer than that and I sure appreciated his not being partial to anyone. Management expected you to do your best at all

times. If you didn’t do it, why in those days just go catch a bus home. Although no words were ever spoken, these expectations were perfectly clear to everyone. But whatever Southworth did say, you could believe. Myself, I thought the

world of the guy."

"He is without doubt the most conscientious and hardest-working pilot in the big leagues," wrote Frank Sargent in the Lowell

Sun. He is a firm believer in the theory that ’if you want a thing done right, do it yourself.’ He does everything from supervise workouts to help move the batting practice screen. He is a stickler for detail."

Nevertheless "Billy the Kid" had his detractors. Among them was Johnny Sain, the team’s meal ticket who led the NL in 1948 with 24 wins, 39 starts, 28 complete games, and 314 innings. In Conatser’s view, he "should have received the MVP award for his achievements that season," especially since they also led the way to the Braves first pennant in 34 years. Instead the award went to an equally deserving Stan Musial who had had a big year at the plate. To make matters worse, a few months earlier the Tribe had signed Johnny Antonelli, fresh out of high school and one of baseball’s original bonus babies, for $65,000. The rookie from Rochester,New York’s contract "appalled" the usually softspoken curve balling Arkansan. Even though

Perini was the final judge on the size of Antonelli’s bonus, according to Conatser Sain thought that Southworth factored in the

negotiations. As Clint added, "it probably wasn’t so but Johnny was disgusted that an unproven kid’s salary was approximately four times his own. Sain is dead now so I can tell the story. I would never tell anyone that before. He just

didn’t care for him at all."

To mend broken fences, the Hub National Leaguers tore up Sain’s old contract and gave him a new one. "I said to Johnny, I hope you got your $45,000. His answer was ’Clint, I wish I was making $25,000.’ I’ll tell you something else I haven’t told very many people. Sain said, ’I hope we don’t win the World Series.’ When I asked him why his answer was ’Well if we do, that little SOB will take all the credit for it.’ And then he goes and slams the door on the Feller in the Series opener. In other words, he was expressing his displeasure with Southworth but still doing all in his power to beat the AL champs."

Known in the media as "The Little General", Southworth was a stern taskmaster and paternalistic in a way that backfired on him at least once. Conatser was roommates with Earl Torgeson during spring training in 1949. "And one evening he told me that he and some of the fellas were going to a particular night club out-of-town. All of a sudden my phone rings. The voice on the other end says, ’Who is this?’ It’s Clint. ’Torgy there?’ No. ’Do you know where he is?’ I don’t, Billy. BAM [the sound of

Southworth slamming the phone down]. He was on a drinking binge and called all the other rooms in the hotel. I found the phone number for this place and told Torgy to get back here fast because Billy was on the warpath. Whatever went on in Billy’s mind was more than the guys going out for a few beers. Maybe he began to lose it there."

In my opinion the "it" that Clint was alluding to was -- the respect of his players. Not advertised openly but well-known by insiders was that Billy had a serious drinking problem which was aggravated by his son’s tragic death four years earlier. Perhaps Southworth did not want his boys (as he called them often!) to suffer alcohol induced setbacks on or off the field.

Says Clint, "I think Billy in his own way had a family-like closeness to his players, although they took it wrong." But Billy was becoming an anachronism during the late 40s. Bill James, in his well researched book on the history of baseball managers, persuasively argues that the rapid postwar growth of cities, new methods of transportation, night baseball, Kinsey’s sex

reports, and most important the core questioning of whether employers had the right to exercise authority 24/7 conspired together to undermine the leadership skills of old style pilots such as Joe McCarthy, Frankie Frisch, and Southworth and to render them increasingly irrelevant.

One reason oddsmakers favored the Indians in the 1948 World Series was their balanced attack. With Lou Boudreau, Larry

Doby, Joe Gordon, Ken Keltner, Eddie Robinson, and Dale Mitchell in the lineup every day, their team could beat you at small ball and at long ball. And Southworth’s team had the misfortune to lose Jeff Heath shortly before the regular season ended due to a devastating injury sustained in a meaningless game. Jeff, purchased from the poverty stricken St. Louis

Browns during the winter, was a dangerous lefthanded pull-hitter who filled a major void in the Braves offense. "I can’t wait to see [him] in action. He’ll be a great help in run getting," was the appraisal Southworth offered of his new acquisition as the Braves got ready to better their third place finish in 1947. And as usual the veteran skipper was correct. Although platooned

in left field, Heath was number two in RBIs for the Tribe in 1948.

On the other hand, before spring training members of Boston’s Hot Stove League second guessed the benefits Heath could deliver to the Allston ballyard due to his alleged role in the "cry baby rebellion of 1940" staged by the Indians. "I don’t know if you are familiar with the story," Clint explained, "but the reason he despised Cleveland was that he had been blamed for the revolt even though he had nothing to do with it. Roy Weatherly (nicknamed Stormy!), one of Cleveland’s outfielders, came

up to him with a bunch of gripes they had with their hated manager Oscar Vitt. So Roy went to Jeff, an established star on the ballclub with an easygoing temperament, and asked Heath to bring the team’s list of complaints to the front office’s attention. When management held a team meeting to get the full picture, all the players became comatose and left Jeff holding

the bag. The press’ spin on the incident pointed a finger at Heath as the ringleader of the revolt. He was actually the last guy in the world to cause an insurrection like that." Southworth’s own comment on Heath’s value to the Braves in 1948 supports Conatser. "They told me when I got him from the American League that Heath was a troublemaker. If he is, I’d sure like

to have eight other troublemakers like him."

Clint and Jeff roomed together that year. Here is his account of the day at Ebbets Field in late September when Heath was injured. "We had already clinched the NL flag. So Jeff goes to Southworth and says, ’Billy, I don’t want to play against the Dodgers today because I hate Cleveland and have been waiting all season for the chance to face them’." [Moreover Heath had

paid his dues, putting in 12 years of service with the Indians, Browns, and Washington Senators for the opportunity to get into the Series.] "During the year he repeatedly said, ’I hope we play the Indians; I will kill them.’ And he could, he was that kind of a guy. Anyways, after you play so many years you just automatically slide but looking ahead at whom the Braves’ post

season opponent might be he said to himself I’m not going to slide. Well he hesitated and when he slid dislocated his ankle. We rushed from our dugout to home plate. Roy Campanella said, Hey fellas, I let him through; I didn’t block him.’

We knew it wasn’t Campy’s fault. It happened before he got that close to the plate. Jeff was in sheer agony. His tibia bone was just sticking out there and you could have taken a pair of scissors and cut off his foot like that. Jeff’s loss really

hurt us because he hit .319 that year. Since I batted .323 against left-handed pitchers it meant we had a big bat in the outfield regardless of who the other team put on the mound. He played for 2 or 3 more years with a huge shoe. But he could never mentally make himself slide again due to that horrible memory." [Note: Heath appeared in 36 games for the Braves in 1949

(.306, 9HR, 23RBI) and played Pacific Coast League ball in 1950. He later became a Seattle TV sportscaster.]

"Not many people know the reason why Southworth wanted Heath in the starting lineup for that game in Brooklyn. Back in 1943 the Cardinals clinched the pennant early with 13 days to go. Billy’s front line players wanted to take a few days off. The Redbirds won only six of their next eleven games, could not regain their cutting edge in the World Series, and were defeated four games to one in the World Series. ’I don’t want you to lose your momentum,’ Billy told us--and that was good thinking on his part." In an Associated Press story datelined September 28, 1948 he added, "I’m guarding against a letdown. Every

regular will stay on the job for we’re out to win everything in sight."

Conceivably some Red Sox players did not know the origin of Heath’s unequivocal choice as an opponent in the fall classic. Frank Sargent wrote that "when the news about Heath’s broken ankle reached the Red Sox clubhouse, not everyone was sympathetic. There were those who sneered at the mere mention of his name. ’He shot off his mouth on the radio didn’t he?’

asked one of the players. ’Well maybe they’ll play Cleveland but he’ll not be there. They’ll get their brains beaten in anyhow.’" So much for the theory of peaceful coexistence between Beantown’s two pro baseball clubs.

Many baseball observers identify Southworth as a manager who played the game "by the book." Local scribes said only in partial jest that "Billy is the king of percentages who must carry a logarithm table around with him." Without question his strategy did rely on bunting ("more than any manager of the 1940s and more than any manager since", according to Bill

James’ research) and platooning (in ’48 with Heath, Conatser, Jim Russell, and Mike McCormick in the outfield; to a lesser degree, Earl Torgeson and Frank McCormick at first base and Phil Masi and Bill Salkeld behind the plate). Yet most impressive to Clint was how much he trusted his baseball instincts. "When I first joined the club, Tommy Holmes told me,

’Watch this guy. He will do things you won’t believe and they will work for him.’ For instance, he would take a guy off the bench hitting about .150 like Bob Sturgeon [whose ’48 batting average was .218] and he would deliver a clutch base hit. He just had a gut feeling about the right thing to do in that situation. The moves he would make would work for him--all the

time, not occasionally. Leo Durocher was the same way. I don’t know what it is. It’s like some guys can pick horses out of nowhere.Southworth was a genius like that on the diamond."

Conatser’s vast admiration of Southworth led him to comment to me in January 2007, "Look at his record. He should be

in the Hall of Fame, no matter what anyone says." And what a record he compiled. His career total of 1,044-704 works out to a .597 winning percentage and places him third best among managers with 1000 wins, trailing only Hall of Famers Joe McCarthy and Frank Selee.Thanks to James’ work, here are some additional stats. Categories in which his teams led the league most often during his 13-year managerial career: hits(6), complete games(6), shutouts(5), batting average(5),

doubles(5), slugging percentage(4), pitcher’s strikeouts(4), and ERA(4). On the flip side, Southworth’s teams never led the

league in saves, errors, or walks allowed. The longstanding oversight that Clint earlier noted was finally corrected when he was elected to Cooperstown by the Hall’s Veterans Committee in December 2007.

Sixty games into the 1951 season with the Boston Braves in fifth place and going nowhere, Billy’s popular rightfielder (who

fittingly wore #1) took over the reins. After managing, Southworth remained with the organization as a scout. Tommie Ferguson ran into him in Waycross, Georgia where the Braves minor league camp was located because Fergie had to drop off there all the uniforms worn by the parent team during the previous year. "Billy had an awfully small room situated in a building

near a prison where each convict escape was the signal to turn on the searchlights and sirens. I said to him - you were the manager of championship ballclubs with the Cardinals and the Braves. Is this the best they could do for you? He looked at me and said, ’Tommie, remember one thing. If you are a big leaguer, you are a big leaguer under any conditions’. And

to this day I carry that message with me about adjusting to adversity rather than bitch and moan."

All’s well that ends well. Although The Little General lost his share of battles, he won the war. And now the baseball world awaits his official induction into Cooperstown on Sunday, July 27, 2008, sixty years after his Braves captured their final pennant in Boston.

Special to BillySouthworth.com, this article first appeared in the Boston Braves Historical Society Newsletter, Spring 2008 edition, republished here with permission